CircumNavigate

By Jill Therrien

May 2015

standing in the East

a needle points West

the Mystery

I head North

then back East

here I stand

at the edge of the compass

and I see all the elements

Dancing

Cosmic egg bursts!

Meteor falls

a basin

Stars

Trees

Wind

arrow points toward chaos

that makes roots look simple in their form

tools that forge, pinch, stretch, wheel, and pierce the sole

or is it my Soul?

Is it your hand

offering me emptiness

so grounded and still

or perhaps it’s the

layers

upon

Layers

pages of everything I have yet to learn

and relics of my history

Yours

Theirs

Ours

my ever fading archive

of memories

all packed into cases

so neatly

stacked

wax molds

an index

cones

toppling over each other

Cones

like my eyes

turning light into forms

into Terra Firma

or stone

or maps

with nothing known

no location to be found

the plates shift

the earth quakes

a temple in the Desert

FOUND

Cosmic tumbleweed

Desolation

Illusion

more scales

Mass

Weight

to the bottom of the Ocean she fell

Sea Sponge holds the Egg

Whole

Perfect

Incomplete

Forms

where do I go?

what must I do?

not always knowing

understanding

waxing and waning

between intuitive TRUST

and the searching—

Endless searching

for markings

directions

symbols

box after box

Book after Book

page after page

HISTORY

His

Hers

Yours

Mine

Ours

…Theirs

Circumnavigate

…circle around

the Mystery

spiraling upward

back down

return East

Rebirth

nothing here is linear

Expand the Horizon to the Spiritual Inlet

On CircumNavigators

By Mark Levy

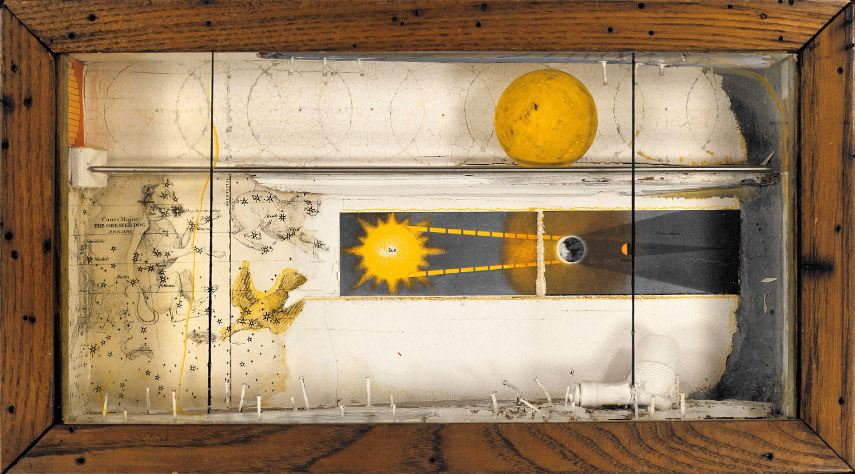

Inspired by the circular configuration of vitrines on their initial visit to the Flora Lamson Hewlett Library of the Graduate Theological Union, Danae Mattes and Christel Dillbohner envisioned a “compass” of made and found objects in each vitrine that would metaphorically and metonymically point to the contents of a library oriented to metaphysical journeys. To use their word, the objects become “Wegweiser,” signposts or signifiers that purport to be navigational clues but are in effect, numinous signifiers without signifieds or specific meanings. Each vitrine of the compass becomes a road going nowhere and everywhere while connecting to the objects in one vitrine to those of another in obscure and indirect ways. As Dillbohner and Mattes write in their statement. “Surprisingly non-linear, the most direct path to a destination may be a circuitous one.”

The assemblages in each vitrine may appear to reference some hermeneutical exercise in philosophy, science or pseudo-science, the landscape of another world, or even some usually unseen aspect of this world, and so forth. Selected from a large collection of carefully curated objects brought together by the artists in the library en masse, the assemblages in the vitrines bear traces of the users of the objects, the makers of the objects, and the consciousness of the artists who selected them and put them together. Some of the objects originally came from the private household collection of the artists so they have strong associations and meanings for them especially as they were often once in the possession of close friends and colleagues. In the end, however, Dillbohner and Mattes surrendered their own claim on the objects as they came together quite naturally and intuitively in new and unforeseen site specific ways.

Thus, circumnavigation occurs here through the time and space of the imagination with its unexpected results, but also intersubjectivity between the multiple human presences and contexts that are embodied in the objects. This intersubjectivity even includes the viewer as he or she fabricates a personal meaning or meanings here.

Indeed, CircumNavigators is a vibrant postmodernist artistic enterprise in which all significations are possible and welcomed. For postmodernist artists such as Dillbohner and Mattes meaning is endlessly deferred because CircumNavigators is a journey toward meaning, not the arrival at a closed absolute truth. As Mattes and Dillbohner eloquently exclaim in their statement of purpose, “The very act of traveling itself may be the actual destination when understood ontologically.”

CircumNavigators invites many comparisons with both literary and visual works of art. In the story “The Library of Babel,” from the collection of Ficciones of 1944, Jorge Louis Borges invents “a circular chamber containing a great circular book, whose spine is continuous which follows a complete circle of the walls; but their testimony is suspect, the words are obscure.” These books, Borges continues, “signify nothing in themselves,” and correspond “to past or remote languages.”

CircumNavigators also can be said to be a single book, albeit with a visual language of free floating visual signifiers that wrap around a spine, – in this case a sculpture by Stephen DeStaebler. With Borges’ story in mind it is both a surprising and felicitous coincidence that this previously installed sculpture has more than a vague spinal resemblance. In any event, DeStaebler’s “Winged Figure” has the look of an archeological remnant like the objects of the vitrines which have or are given an aged patina, making them seem like an archeological remnant of a remote civilization or civilization of the future that has become archeological.

Borges’s Library of Babel is similarly “ab aeterno,” from immemorial time, as he puts it. Of course, the signifiers of CircumNavigators lead to imaginary stories unlike the unreadable book or books of the Library of Babel.

Perhaps then, Circumnavigators is closer to Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities” (1972) in which the author imagines the fantastic tales told to the Emperor of China by Marco Polo of the places he visited.

At first, each tale appears to emerge ex- nihilo from Calvino’s fervid mind but on closer examination the stories originate from fragments of Calvino’s consciousness that are recognizable and are repeated in different stories. In CircumNavigators Mattes and Dillbohner present objects, including cones, rectangular boxes, cylinders and spheres of all kinds, old measuring devices, mirrors, etc. that are also repeated in several vitrines. Both “Invisible Cities” and CircumNavigators celebrate the creative ability to fashion multiple stories, but there is also the fragments from which the stories come from, a common circular story as it were. This is the deep level of consciousness from which stories emerge. Of course “Invisible Cities” is a modernist novel rather than a postmodernist text; Calvino tells the stories while Dillbohner and Mattes encourage the viewer to do the storytelling.

CircumNavigators also has connections with other visual projects. Dillbohner’s previous and current boxes and installations are informed by an innovative use of unusual materials including twigs, clay salt, beeswax, discarded parts of furniture and electrical apparatus, etc., that have been garnered over decades.

It is no surprise that an influence on her work has been Joseph Beuys whose use of materials such as wax, felt, and fat, transformed German sculpture and performance art after the Second World War. In turn, Beuys’ sculptures, installations, and blackboard lectures manifest the influence of the anthroposophist and Naturphilosoph Rudolph Steiner’s quirky scientific and alchemical experiments. In the vitrines of CircumNavigators, there are deep references to Beuys and Steiner in the use of worn scientific apparatus, measuring devices, and natural objects in varying degrees of decay and corrosion.

The desiccated landscapes these objects inhabit in the vitrines as well as Mattes’s wall mounted painting/clay sculptures also suggest the metamorphosis of ancient diluvial events in their subtly raised, cracked, and mottled surfaces. These surfaces magnify the sublime landscape elements of the painted aspects of the works: the illusion of endless space and emptiness, form becoming formlessness, natural light becoming metaphysical light, and so on. Watery occurrences are a significant theme in Mattes’s works.

In the Evaporation Pools, for example, liquid clay creates layers of fractal patterns as it gradually hardens. To be sure, Mattes and Dillbohner have been enabled to share their penchant for the marks of transmutation and age in Circumnavigators.

There are still other visual references here. I am thinking of Anselm Kiefer’s ignitable fields and forests that sometimes turn into ash as well as his fascination with rubble. Both Dillbohner and Kiefer grew up in the ruins of Germany after the Second World War. In Kiefer’s oeuvre and in CircumNavigators earth and rubble are a basic grounding element, a beginning as well as an ending from which, in Kiefer’s words “the incessant metabolism” of things evolve. In CircumNavigators, there is the sense that these objects, unearthed but still connected with the earth, are material remnants of cities/civilizations that no longer exist, or never existed except in the imagination. But together for the first time in the vitrines they often awaken into new aesthetic and conceptual ensembles.

The juxtaposition of unrelated objects that occurs in a number of the vitrines in CircumNavigators also relates to Surrealism. The Comte de Lautremont, the pseudonym of Isadore Ducasse, a precursor of the Surrealists wrote in his “Chants de Maldoror,” (1868) “beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella”. This phrase is at the core of the ideology in Surrealist manifestos written by the founder of this movement Andre Breton in the 1920s. He believed that the juxtaposition of unrelated found objects had the potentiality to project the viewer out of ordinary consciousness into non- ordinary realities. Eventually found objects were picked mostly for their aesthetic qualities in Surrealist collage and assemblage.

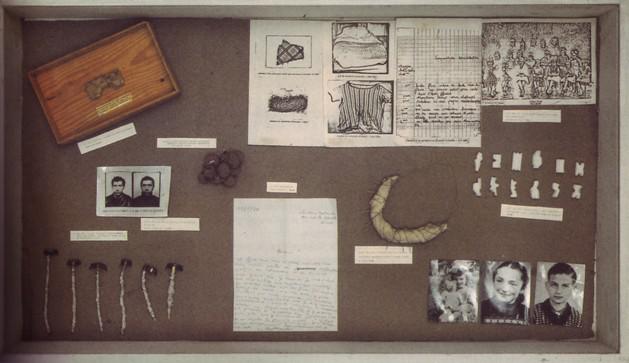

In addition to Surrealist works of art, CircumNavigators reminds me of the Wunderkammern, the marvel or curiosity cabinets that date from the Renaissance and are the precursor of the modern museum. These cabinets contained natural objects, small statues from foreign lands, and strange man made objects. Often a narrative description was not attached to the components. The French artist Christian Boltanski created an updated variation of the Wunderkammern in 1970 called “Reference Vitrines”. They are based on his fascination with the display cases at the now closed Musee de l’Homme, the anthropological museum in Paris in which the ethnographers wove a narrative description about a particular tribe from unfamiliar tools, diagrams, and labels.

In Boltanski’s Vitrines, however, bizarre found objects and objects made by the artist, photographs of him and family letters, etc. are presented. While Boltanski refrains from specific narrative connections, unlike the ethnographers of the Musee de l’Homme, a sad story can be inferred by the viewer as there are slipping references to his harrowing childhood hiding from the Nazi’s in Paris. To be sure, closure is deferred as in CircumNavigators, but Dillbohner and Mattes do not impose a heavy personal agenda on their objects, so they allow for more open-ended significations and stories than Boltanski. Nor do Mattes and Dillbohner create just another vault for the housing of objects, but another expanding library as it were, nestled in a library.

Instead, CircumNavigators is the organic kernel of a living project. Now, under the auspices of a website, CircumNavigators continues to be a compass where online contributors can create their own points in conjunction with the original library installation and those of the other contributors.

Of Rust and Dust

By Didier Maleuvre

Ruins are back. Once again we welcome the withering kiss of Father Time and huddle under Chronos’ verdigrisy wings. An “enormous appetite for ruin imagery” is, some say, the rumble currently in our cultural belly. Rust lust, ruin porn, memory fever, commemoration obsession: the culture of remembrance will satisfy every retrocognate need. Our idea of winding down is to rewind. Winter fields of ashes and debris; horizons sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, inked in memory, speckled with the charcoal of crimes past, your golden hair Margareta, your ashen hair Shulamite. Never since the great Romantic spree of remembering have the feel and look of the old, the charred, the ruined and the pulverized seem so rife with aesthetic frisson. And with the “griev’d voice of Mnemosyne” (Keats) growing so loud, and the call to remember so symphonic, it is hard to make out just what you are meant to remember. Perhaps we must remember to remember. We must remember that there is memory out there. For remembering is faithful and steadfast and true. Those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it, warns an old (handsomely rusted) saw. Remember, then, so you may break free. Of course there is no guarantee that escaping the past won’t induce us to forget it, which will lead us to repeat it, and so on and so non-forth.

The Romantics put remembrance to another task: not liberation but libation. They remembered for the sake of it; they remembered because memory was more poetic than prognostication. “Sometimes a lone column rose in a waste land, as a lofty thought sometimes soars in a soul ravaged by time and sorrow,” says Chateaubriand ambling over the scenic Forum. Sometimes it is enough that a ruin makes you think. As to what that lofty thought is, well, it would ruin the poetry to go too much into details. Mnemosyne, vestal of memory, not Clio (history’s schoolmarm) is the spirit of our memorious age. The poeticness of the old isn’t about the contents of the past; it’s about the sheen of the past—or rather, its skin cloudiness, its pale freckle, its patina.

“The greatest glory of a building is not in its stones nor in its gold. Its glory is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy… It is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look for the real light, and colour and preciousness of architecture.” This is Ruskin fluting his antiquarian love of old buildings whose medieval creators, no doubt, would have felt no small bemusement at the notion that the moulds mottling their once gleaming abbeys (which they called opera moderna for a reason)—that all this would someday be handsomely touted as the “golden stain of time”. Medievals didn’t go at all for that stain. Nor indeed their olden forebears. However far we cast our eyes back into history, it’s the love of shine that predominates.

The ancient Greeks liked their statues and temples bright, gleaming, gaudy and looking spanking new. To prevent discoloration, they coated marbles and bronzes in bitumen. Likewise the Romans daubed their sculptures in ageless gold and followed Pliny’s opinion that, on a statue, any hint of patina looks vile (aerugu virus). As for the medieval eye, whether low Latin or high Gothic, it harkened to gleam and sparkle. Things, perhaps, took a turn during the Renaissance. In 1337, Petrarch bagpacked and bivouacked among Roman ruins and antiquities with keen interest. He pointed out that the stone trough used irreverently by the cowherd was once a sarcophagus. He is the first throb of our modern love affair with ruins. Many imitated him. Freshly unearthed, restored and re-limbed, ancient statues became the collection prizes of princes and popes. The antique style came in vogue. Actually it was rather more the style, not the stain, of antiquity which charmed Renaissance humanists. Patina added little aesthetic value to ancient artifacts. It was something to put up with—and sometimes not, as witness the vigorous scrubbing to which ancient busts were often treated. There is the anecdote, mere hearsay, of Michelangelo interring a fresh new sculpture in order to “discover” it later and palm it off as an ancient find. It is not said whether the buyer had the piece buffed to a shine before showing it off in his palazzo. Given the preference for flash over fungus, it is not improbable.

For the look of the old, that is, the aged look of the old, to become eye-worthy, one has to wait for the age of art collecting which begins in the late seventeenth century. It is then we find the first printed mention of the word “patina”, in a treatise on art of 1681 by one Filippo Baldinucci. Patina, Baldinucci says, is “a term used by painters, which others also call a skin (pelle), namely that general, dark tone which time causes to appear on paintings, that can occasionally be flattering to them”. Note that the look of age can be “flattering”. As to whether it flatters the appearance of an image or its prestige, by anointing it with antiquity, Baldinucci doesn’t say. But threescore years later, the Enclyclopédie is categorical: the veneer of age, regardless of its damage to the artistic appearance, is a boon. “There is no French word to express that beautiful and brilliant color of verdigris… the attractiveness of this color to the eye and the difficulty in describing it is highly valued by the Italians who call it patina.” The time is mid-eighteenth century, the fever of art collecting is in full swing. Every great house in England wants its own cache of antiquities, and Italian dealers send northward every wax-coated, tallow-yellowed, worn and weathered Madonna or Antinous or cassone there is to be begged and bartered. Patina is the seal of authenticity; it is real; it is also honourable, a symbol of the hallowed link to the past—a past so rudely shunted aside by the steam engine, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic state and the Anglo-Saxon cash nexus.

In comes the age of Chateaubriand and his pensive column, of Keats’ “grey cathedrals, buttress’d walls, rent towers, the superannuation of sunk realms… the faulture of decrepit things”; the age of Hubert Robert and Caspar David Friedrich, of Piranesi’s handsomely drawn rubble, of a whole cottage industry of ruin pictures to adorn the walls of every genteel home from Aberdeen to Bordeaux. The tired banker looks up from his newspaper to momentarily muse over the fall of empires, ponder the vanity of human endeavour, tremble at the impermanence of civilization. The pose just begged for a lampoon. “There’s a fascination frantic/In a ruin that’s romantic,” sang Gilbert and Sullivan to giggling Victorians. And well might they, for an industry of patina kitsch was by then doing brisk business. “To patinate” and “patination” entered the dictionary in the nineteenth century, confirming the general acquiescence that what Chronos took eons to concoct clever humans could conjure up in a trice. Hogarth, back in the eighteenth century, had drawn a cartoon of Father Time “smoking” a painting with his pipe to lend it lucrative patina. It was satire. A century hence, it is with no satiric intent whatever that, to hasten handsome corrosion, Rodin invited his workshop assistants to pee on his bronzes. Rodin had no wish to pass off his sculptures as anything other, or older, than his own. It wasn’t the authenticness, prestige, or resale value of antiquity he sought; it was the look of it. Patination was part of the artistic toolbox. In Paris, professional patinators set up shop yellowing and burnishing modern masters like Degas whom everyone knew to be a contemporary painter. It is as though patina had come into an aesthetic value of its own. Ruskin’s golden stain of time, it seems, had sipped into the very flesh of art.

It’s a complicated relation between patina and modernism.

On the one hand, the modernist avant-garde declared freedom from the past. It was all about making tabula rasa, renewal, primeval leaps into the not-yet. It begot constructivist purity, geometric rigorism, stainless steel, the romance of chrome and plastic, the Teflon grace of Bauhaus and the International Style. O Death be not proud for there is no crack, curve or cranny for thee to press your rust on the cheek of a Brandt teapot.

On the other hand, modernism was also an attack on the academic establishment, which means a repudiation of the ideas of gloss and finish. Rejecting the aesthetic of immaculate creations, the modernist jerry-built with salvage, found objects, derelict odds and ends. The more used-up and humble, the better. Thus the look of the old—refurbished in the rhetoric of waste, rusticity and pre-industrial ruggedness—stole back into modernity. Flotsam and dross, yarns, rags, cardboard, straw and dust, rust, scum and sediment; scorching, desiccating and oxidizing; the leprous wall and the carbuncled crust; the abscessed canvas cured in embalming wax, the blister that tells of ancient fires, the palimpsest creaking with the varnish of ages: these became the materials of artists who verily carve and paint and dream patina (Art Brut, arte povera, Tàpies, Kiefer, Fontana, Dubuffet, Beuys, Cornell, Keinholz, etc.). This is not an art of ruins; it is an art in ruins. There ruination and faulture are the expressive media.

Why this passion for corrugation and craquelure, for frittering and corrosion? Why ruin art?

One explanation is reaction. In the twentieth-century the artist is fighting a culture-wide onslaught of gloss and sparkle—the bullyingly buoyant, wrinkle-free DayGlo eden and timeless noonday of consumer imagery. To counter this terror campaign of optimism, what is the serious artist to do? There are some artists who surrender to the blitz of gleam with a tongue permanently in cheek. They crank up the gloss to unchartered highs on the kitsch meter. They play court jesters—basically the job of Pop Art and postmodern epigones. Other artists react by tacking full tilt against the wind. They coat even the present in the rags and rusts of antiquity. Against the perpetual grinning adolescence of consumer culture, they want to remind us that we age. Absent the tragic reminder that we die, human life is a shapeless, maudlin lie. Ruin art speaks of mortality. It defends the “soothing thoughts that spring out of human suffering”, the “faith that looks through death”, the “years that bring the philosophic mind” (Wordsworth). We have not yet reached the age of agelessness. We are not titanium-clad manga gods (Murakami) or chrome rabbits and gold-plated teddies (Koons). Patina art is the recognition that we are still (if only for a while longer) the children of nature. Ruin art is the swan’s song of an era, soon to pass, in which people naturally grew old, nay, were allowed to die.

Patina, rust, decay: what are these if not nature reclaiming what is hers? They are the signs of nature taking us back into the fold. With age, the vainglorious sculpture gains the roundness of a pebble; carpentry acquires the polish of jetsam; barbed wire takes on the innocence of twigs. Nature welcomes us back, rounds our angles, smoothens our swerves and missteps. It dabs on civilization the sacrament of mortality.

Ruin art is also recognition that memory isn’t what it used to be. Something unprecedented indeed has happened to memory in the last quarter century. It has become disembodied, removed from its old physical vessels and transformed into data—bits and bytes which unlike the page will never yellow, and unlike vellum will never crack, and unlike the stone will never flake and crack. The past—this is disconcerting—need no longer age. It need no longer look like it comes from afar.

Patina, on this score, is there to restore the remoteness of the past, its aura, its haloed horizon. It reminds us that what we remember is almost by definition out of reach. Patina art reflects on current preoccupation with the state of memory which is probably on the cusp of an immense technological transformation. Ruin art looks back to an age when objects enjoyed the adventure of getting lost—an age when forgetting twined around remembering, when the pang of loss touched, and blurred, the mirror of remembrance.

As such, patina solemnizes a process of remembering which is trivialized by digital instant recall. For digital memory hoovers away the dust of the generations of rememberers who have carried the past up to us. It cuts an electronic beeline from now to then; it blasts aside the old meanderings of retrieval. The archive becomes data, disincarnate and ubiquitous. Gone are the fingerprints, the dog-eared blemishes, the marginalia, the archival dandruff, the scrapes with destruction, the near-misses, the erosions of happenstance which curation deposited on the past. The digital past never had to cross the wide Lethe; it owes nothing to the ferryman; it is removed from the vagaries of human conveyance—it is a past that has not had to travel. Perhaps it is the harbinger of a day when, having done away with the physical couriers of the past, digital memory will eradicate its rememberers too. Having become spaceless, the past may next become memorist-free. Remember the past? Machines will do that for us. Someday perhaps patina art will stand as the quaint, perhaps undecipherable, reminder that there was once a time when the past gathered dust on the road—and that there once was a road.

Ruin art not uncommonly comprises found objects, objects that are the gifts of luck, objects which, in order to be found, must have been mislaid, perhaps even lost, surely discarded and forgotten. Found objects show up the tenuousness of our link to the past. Had our footsteps veered by ever so little, we might never have known them, and they would never have been found. The art of found objects thus sensitizes us to the fragility of remembering—the very fragility destroyed by digital memory which, for one, never misplaces items. Once committed to the digital archive, fragments of the past are forever “backed up”, impossible to lose again, universally accessible by the click of a search button everywhere on earth. The great digital morgue has a drawer for everything and nothing is ever mislaid. Hence, by the same token, nothing is genuinely chanced upon: it is retrieved, called up, linked, co-tagged.

The art of the objet trouvé, on the contrary, luxuriates in the gaps and ravines of history. It is in those hollows that objects gather rust and dust. How was that object lost? Why was it misplaced here and not there? Of such questions stories are made. A found object is like the fragment of a poem waiting to be written. What is the filigree that connects this red-dusted chisel to that curl of meshed plaster? They seem to call for a story yet to be written. On the contrary, it is a question whether storytelling will survive the age of the age-proof digital archive. The disincarnate library of Babel remembers every thing with pin-sharp precision. It is like Funes the memorious, the character of Borges’ tale, who has absolute recall of every single thinghis senses have ever landed upon, not matter how small and fleeting. Yet, because he remembers every last thing, Funes cannot tell stories. His mind is a honeycomb of singularities; he has no need to liken and link them. Narrative thought, presumably, was born from a defect of human memory: it’s because we can’t remember everything, because the mind loses the trail of a list too long, that we lump and latch things into family trains, and have use for thinking, which is but to tell stories about what we all too scantily know.

Ruin art is about the ways of journeying between lost and found. It entails space. After all, patina is texture, and texture means the stretching and hollowing of materials. Porous and fraying, vitreous or gossamer, patina cues the eye to the inner flesh, into the vertebration and nervature of things. It speaks of the fabric under the luster. Patina is matter matting over transparency, it is medium taking over the message. Against transparent representation, it insists on the obduracy of the material. Not for Narcissus the cloudy, bleary, cankered surfaces of patina. They are poor reflectors. Mirror, mirror, tell me how old I am.

For patina is a tired face. It is distress, material fatigue. It is a suffering surface that admits stress and surrender. It may be—should we speak as Zarathustra spake—a sign of decadence, an admission of our impressionability, proof that we invite contamination, the frisson of absorbing and being absorbed. For a good reason do we call those media mixed. On a more enthusiastic note, on the contrary, patina celebrates mixture. It was about letting the outside, the stranger, come unto us. It eulogizes acceptance and the moral beauty of hybridity. Patina gilds a society that prides itself on being inclusive and broad-minded. Blight, in this sense, can be a form of bling.

There is patina that speaks of our presence (a door handle polished by centuries of hands, a doorstep hollowed by the shuffle of ancient feet, the well-worn leather, the dimpled pewter); and there is the patina that speaks of our neglect and absence (a rivet retrieved from a bog, the rusted plough deep in the brackens, a marbled shoetree, a frayed fence, the bleached bones of yesteryear’s bustle). Nothing so fascinates us as intimations of our absence. Where were we when nature overspread our pavements, sank our houses, and buried our tools? It is as though we fancied ourselves the survivors of a great flood—call it our great disappearance. Over your cities grass will grow…

Ruin art is about what happened when we weren’t looking. Perhaps it is a way of imagining the world without us. There is an aesthetic theory going back to the Italian Renaissance which says that beauty in art is achieved when all traces of manufacture are smoothed out of view. Beautiful is the ostensibly made object that looks as though no human interfered in its making. It seems effortless, self-evident, natural. Art, in this light, revolves around our pretending not to be there, the fantasy of our absence, the world restored to the pre-Adamic garden. On this score, it may be that patina art or ruin art connect with this most classical of art’s ideals, i.e., to create a human-made expression seemingly unspoiled by human hands. Objets trouvés, after all, were all about to minimize the artist-as-maker, almost to whittle his presence out of view. It was about the death of the artist. With ruin art, the artist returns to romanticize his own vanishing, now greeted as a kind of self-liberation, as transcendence.

Ruin art—an art in dust—romanticizes our survival. Before us the deluge. We picture ourselves picking over a scorched and flooded earth some indefinite time after the great blast. Over our cities the grass is growing. We are the survivors of a nearly extinct race. What race was it? Oh, one that bustled and fretted a great deal, and fussed and feared death. The dials of broken clocks stare out to a time before humankind began counting time. Ruin art prefers prehistoric long duration over the stopwatch society, deep time over bite-size time. It invites us back to an age of open-ended, uncompassed, unclocked wandering. The stars and the horizon, the fatigue of our feet and the pull of our oars are once again our pathfinders. Physical endurance is once more the map-maker of reality.

Of course, ruin art is a wishful dream. It is escapism to a time of earth-bound adventuring, before global positioning satellites tied the earth flat on the gurney of mathematical coordinates. We who root around in the fens are dots of that grid. Ruin art is nostalgia for the earth. It is inescapably pathetic. But pathetic is Greek for “sensitive”, a derivate of pathetikós, “liable to suffer”. Patina is about surfaces responsive to suffering—literally so: dyed, furrowed, and distressed. It is the reminder that something was lost along the way. What will happen to our forms and expressions, our systems of knowledge, our artifacts and buildings when even the possibility of loss and forgetting and want, hence all suffering, is eliminated from human experience? A cognitive society that feels nothing of what it does not know, and hopes and fears and misses nothing, is denied the ecstasy and agony of space- and time-bound existence. Suffering is as alien to it as non-suffering is alien to us. It knows nothing of the poetry of horizons. Isn’t there a risk that the more we obtain our sense of the world from the eyes and ears of algorithms that either cannot forget or do not know if and when they forget, the more we, like those AI’s, will no longer know that we don’t know? Then the glow of pathos and mystery will pale from the world. Ruin art hangs on to that glow. It reminds us that the four dimensions of spacetime need the fifth one of patience and suffering to make a full-blown reality. A world without distressed surfaces is very flat indeed.

NOTES:

1 Dora Apel, Beautiful Terrible Ruins: Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline, p. 9.

2 François-René de Chateaubriand, René (1803).

3 John Ruskin, “The Lamp of Memory”, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849).

4 Filippo Baldinucci, Vocabulario Toscano dell’ Arte del Disegno (1681).